Writer’s block is brutal, especially when you’re opining on a subject with reverence and the only thing more overwhelming than feeling self-conscious about your choice of words is the pervasive push of the delete key. A friend once told me that allowing someone to read the words you’ve painstakingly written about them is akin to walking into a room naked and having them comment on your appearance. Every metaphorical fold, wrinkle, freckle and mole is laid bare for scrutiny and you hope in the end you’ve done your subject justice. Lucky for me, WET Magazine’s founder, Leonard Koren, and I have a lot in common. We can not only relate to the former but as writers also fully appreciate the metaphor of naked vulnerability.

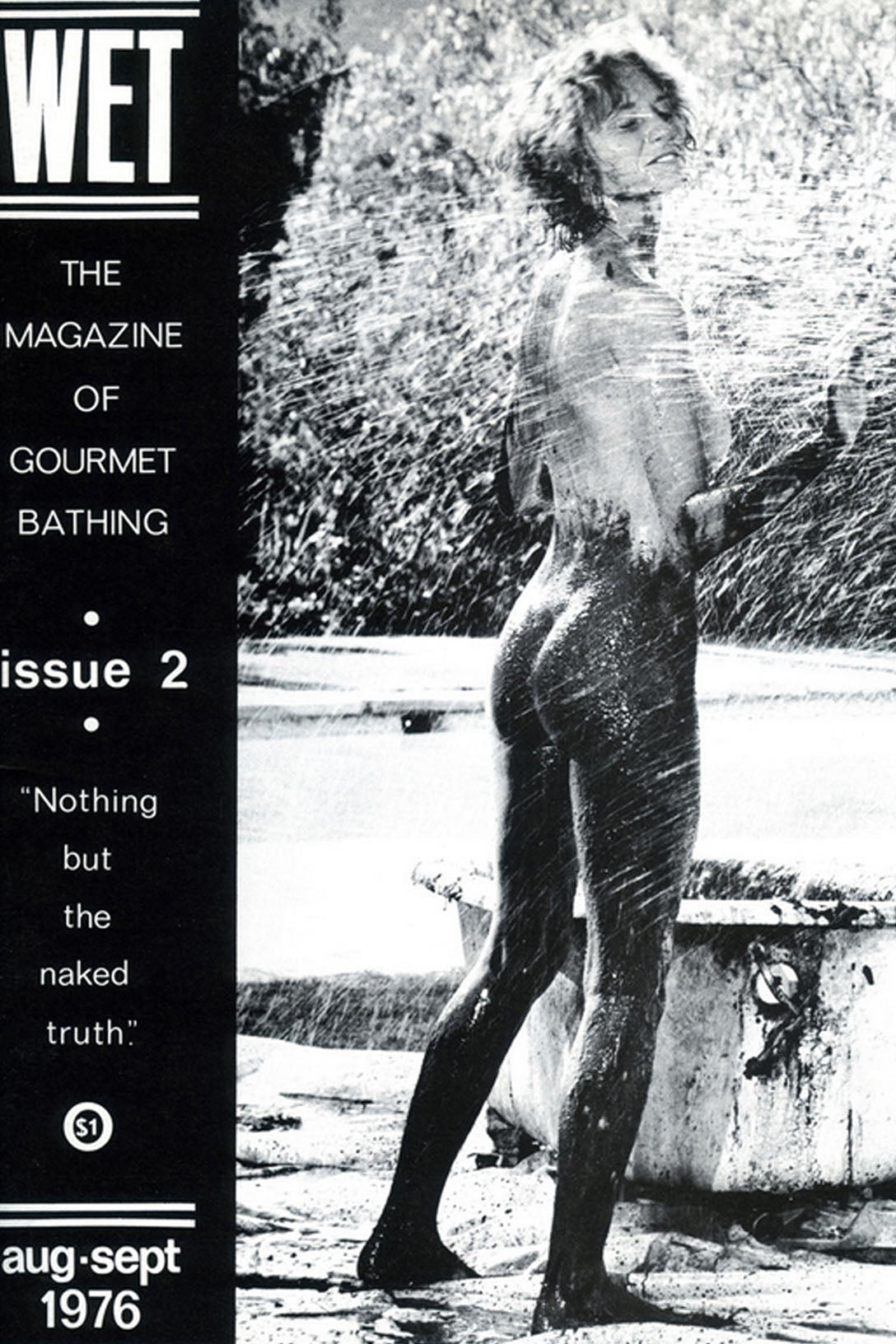

Like all of us, Koren’s story started in water. The native New Yorker was born around the time that post-war America was liberating itself from its puritanical aquatic costume. True story, the daring invention of the bikini was only two years old when Koren came screaming into this world. Little did he know the two would eventually have so much in common.

While many kids cooled off in the streets of New York City, Koren and his family had already made their way west, calling sunny southern California home, the epicenter for the tan and tone. A lifetime of observation in the world around him eventually led to an interest in architecture but only in graduate school did he dip his toe into the ways a human being not only naturally seeks out water for sustenance but as a way to return to our most primal need for self coddling.

A conscious choice to do so informed Koren’s distinguished introspection into the art of bathing routines whether in water, hot humid air or mud while he observed and photographed his friends engaging with the elements. The integrity of the negatives stayed intact but he chopped up the prints to create lithographic and silkscreen art. Friends and local galleries purchased those works but whether he knew it or not, Koren was unintentionally paving the way for a broader way to tell the story of ritualistic bathing with an eye popping graphic vocabulary.

After throwing a Bachinalian thank-you party for all his loyal subjects at the famed Pico-Burnside Baths—a nondescript Russian Jewish bathhouse equidistant from the beach and downtown LA—Koren was lauded by his friends and the art denizens who had so willingly become his subjects. As Koren reflected on the happening during a regularly scheduled afternoon soak, the idea of WET Magazine was born.

The risk was immediately validated as a worthy pursuit. After all, it was the 70s and Koren’s influences were not only rooted in global aesthetics but he could borrow from the proven resonance of big circulation publications like Vogue and Andy Warhol’s Interview that typified the taste at the time. But pitching a small story about his bath art to either of those mags wasn’t interesting enough to Koren; he saw the high water mark that defined pop-culture and knew he could raise that through a niche perspective on the art of “gourmet bathing” with a splash of content you wouldn’t expect to see in any other rag and if you did, Koren or his staff had put a spin on it.

“I rarely tried to define the term,” Koren said when I asked him how he personally focused the editorial mission around the idea of a luxurious soak. “Gourmet Bathing” just seemed like the right conjoining of words at a particular moment. Gourmet bathing never had a static meaning. WET readers were non-linear types, that is, people who understand abstract notions without having to have them explained. If someone needed a definition of gourmet bathing, it was unlikely they were a WET reader.”

In the beginning, there was no benefactor channeling cash to the budding publisher, let alone a staff to make the first issue loud enough to earn the attention of an angel investor. This was probably intentional, as those stuffy money types would not only have wanted a say but would likely make haste of a return on investment, a kiss of death for most creative endeavors needing the freedom to self-actualize. That’s exactly what WET did. The magazine instead existed completely laissez faire and became a magnet for creative collaboration. Quickly, hybrid roles were developed between editorial and ad sales, photography and subscription services, crowdsourced creative direction and hand delivery subscription fulfillment all under Koren’s watchful eye.

While water was the through line for the content in every issue, WET quickly became a well-spring for a regular crew of disobedients who were eager to share their stories from the deep end of creative culture. Simpsons’ creator, Matt Groening donated comic strips. Legendary ceramicist, Peter Shire designed party fliers and calendars. Photographer, Herb Ritts shot editorials, and a revolving door of regular staff of writers, designers, illustrators and luminaries kept things fresh. WET was quickly regarded as a cool culture bible for well-established voices and up and coming creative disobedients. “An endless stream of young talented creators coming though WET's office doors was the magazine's lifeblood,” affirmed Koren.

“During its moment, WET was an important venue, particularly for young, talented, ambitious creators in L.A. and New York,” he explained further. “I don’t remember specifically how Peter Shire became involved with WET other than I liked him as a person and I really liked some teapots of his that I had seen. So I photographed them for the magazine. Other creators, like Matt Groening, simply called and asked if they could come by to show their work. Brilliance was rather easy to spot.”

Throughout its production, WET was headquartered in Venice Beach, a town that shared a similar dejected demographic to a lot of Southern California seaside towns—lands of lost hopes and mothballed dreams. But both Koren and the magazine flourished in this environment. “When the WET office first opened on the corner of Windward and Pacific, Venice seemed like a charming slum by the sea. Besides ocean, what made Venice very special was the abundance of artist-type people, both young and old, who had fascinating studios behind totally nondescript façades. Venice was not a place many people went unless they had business there. This gave us Venice residents a remarkable degree of freedom to do things that would have been difficult or impossible in more established, conventional areas of L.A. Venice then was the perfect place to incubate WET,” added Koren.

With an official office and a steady rotation of devoted staff members, WET was on the creative community’s radar, as was its guerilla methods of marketing. Poster campaigns and t-shirts certainly played their part in the phenomenology of WET’s popularity, as did the proof of Koren’s previous concept that if you throw a great party everyone is your best friend. WET had a lot of those—parties and best friends. However, the problem with publishing is that a number of extraneous factors can prematurely write your obituary.

While WET was considered cool by just about every reader that thumbed through its pages, behind the scenes it succumbed to the financial torture of death by a million papercuts. Like with any indie mag, revenue ebbed and flowed and when WET was flush with cash, everyone celebrated by adding more pages, increasing circulation and perhaps the first nail in the coffin, added frequency. The pressure of trying to keep things fresh and a culmination of other factors seemingly out of Koren’s control, put WET in a position to go out on a high note. As quickly as the magazine dove into the deep end, the final ripple lapped on the tile after six raucous years in business.

Could WET exist today? “Not in the same way,” added Koren when I asked. “The form and content of WET would have to be entirely different in order to stand out—and make sense, or non-sense—in today's social and media landscapes.” I think what he means by that is the world is radically different these days. There isn’t much that can exist in a vacuum free from the court of public opinion. In a sense, magazines like WET serve as a reminder for a time that naked vulnerability was celebrated—not mocked—and privacy allowed ideas to incubate in a way that was free from rapid fire stimulation. Each issue lives on as a time capsule for that era and certainly a paginated homage to gourmet bathing and creative expression.

This story was written by Dustin A. Beatty, the founding Editor-in-Chief of Anthem Magazine that was heavily influenced by Leonard Koren’s WET Magazine.

Visit the archives at the WET Magazine website.