The first thing you notice about the venerable Charles Hollis Jones are his socks. They are, much like the man and his work, a stand out. They are highly sophisticated and exuberantly tasteful but not without a sense of humor and magic. Such is the work, life, and personality of the man they call Mr. Lucite. Although in my experience working with and talking to the man, that moniker leaves so much out.

What you immediately are attracted to with Charles is his warmth, a feeling like you know this man; he could be either your father or the elusive astronaut guru who you believe has the answer. He tells you things like, “I don’t like art that you can’t bump into.” Or when asked about what the secret to a lengthy career is, he responds as if it is obvious, “You have to learn how to milk a cow.” One has the sense, or perhaps the hope, that these answers will echo later in life and reveal something about existence that had been staring you in the face the whole time. He has the wit, the charm, the sense of humor that only comes with the confidence of having been lauded by the Smithsonian for his vanguard exploration of the acrylic and Lucite medium.

For a moment imagine yourself walking into Frank Sinatra’s home for cocktails at sunset to be met with Lucite armchairs that cradle the warm glow of dusk and return it to the scene with an almost fluorescent treatment. Think of Tennessee Williams at home, nestled in the Wisteria Chair he commissioned from Charles, Michael Feinstein and Liza Minnelli belting out cabaret at the Mondrian lit by Charles’s lights, or an ad man casually leaning into the bar at the Playboy Club to order a Manhattan, resting his perfectly cuffed grey flannel pants on a bar stool dreamt up by a kid from a small farm town in Indiana. As such, Charles has etched out a place for himself and his work that positions him at the top of a game that not many can or even dare to try and play.

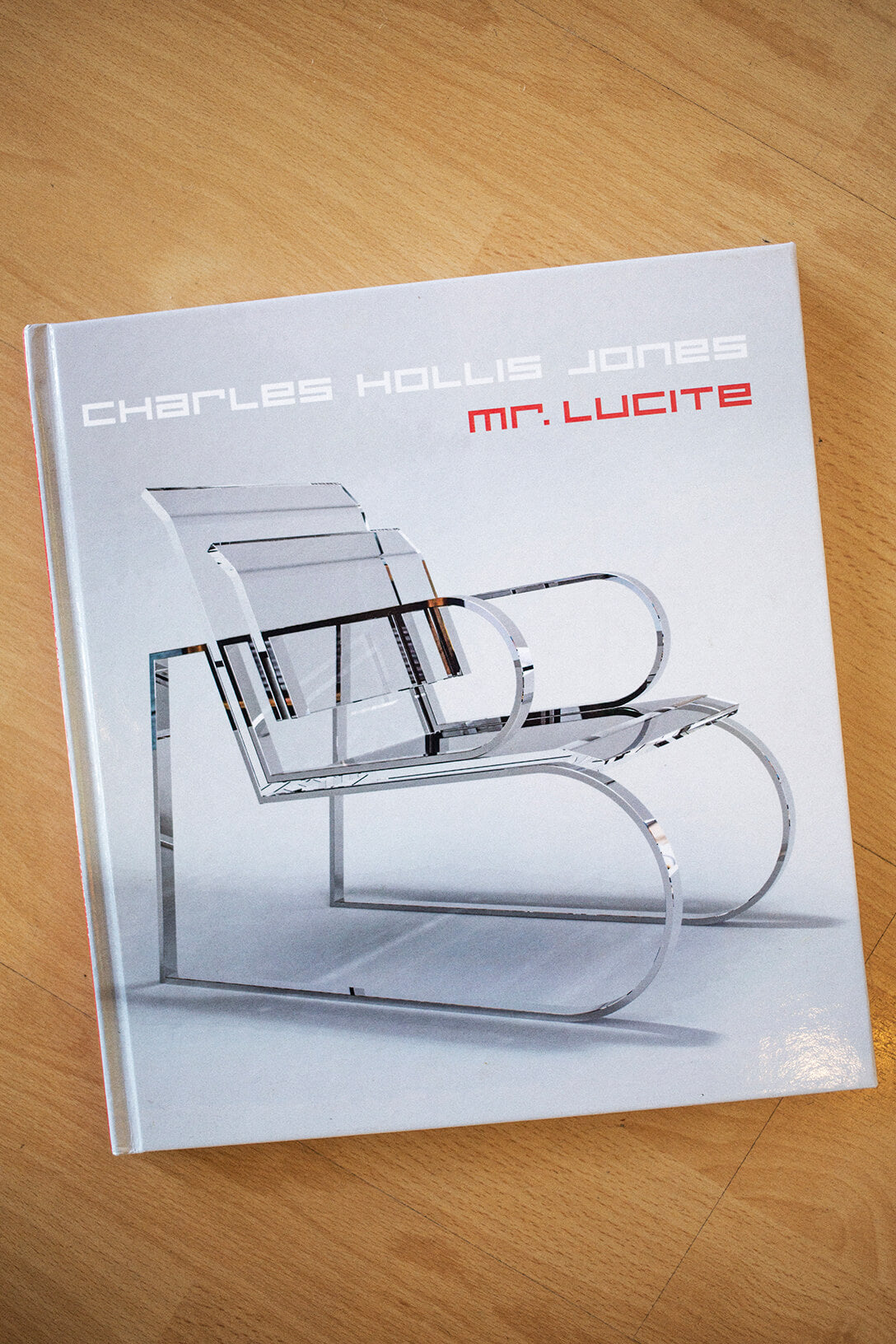

To sit in a Charles Hollis Jones chair is to feel both vulnerable and assertive at the very same time, a sensation that can be intoxicating. It harkens back to a nostalgia that hasn’t even happened yet, and in that, it time travels. It exudes sensuality and sophistication. Set a Charles Hollis Jones chair down in any room and the space must now conform to it, not the other way around. Charles’s chairs are like the beautiful person in the party you are too intimidated to talk to, the one you still dream about long after you’ve left. Jones’ work is starkly, confidently Americana as much as say, Rockwell or Hopper, but perhaps from a parallel dimension. It’s the more magical, cosmic side, also an ode to the good life that Americans were both promised and desired, luxury and leisure that was the golden goose of a metropolitan, hard work ethic. There is both a hardness and plushness to Charles’ work that defines a side of Americana not often investigated or embraced, but is very much the spine of it all. As Charles tells us, “Johnny Carson looked at my work and said, you were raised on a farm weren’t you?”

Hard edged but undulating and soft, smooth, clear, blindingly so, but also a distortion and refraction of light, prismatic, wildly colorful but mostly monotone. It is those extremes that punctuate Charles’ lounge chairs, his lamps and tables. The simplicity of his work is not only vital, it is divine. That tonality is evident in his style of dress and the way that he holds himself, but he is still very much warm. Perhaps it is the Hoosier in him. Charles’ art is hardwired into the memories of his family, almost like a revolutionary homage to them and how they shaped his imagination, his consciousness. The cascading edges of his Tumbling Block line of furniture are a call back to a pattern he found in his mother’s quilts. Lucite was a medium that was attractive to Charles because it wasn’t wood, which his father worked with, and it wasn’t metal, which his brother worked with. It was his own, it was unique and stood out, spoke to a sense of translucence in vision and sculpture but also in experience and relationship. It was at once traditional and unorthodox.

“When you look back at people’s life there’s a lot of relationship and family but words are not allowed and you get along somehow by maneuvering, you don't get around by being clear, there’s a lot of impliedness. Acrylic was important because I wanted to see through everything that was there.” Perhaps the ultimate bit of coaching you can take away from a man who works to help people find their self expression is that you can mine those early experiences for inspiration. As Charles tells it, “Here’s what happened: I was dreaming all the years like at 7, 8, 9, 10. I was dreaming all these lines intersecting, all these patterns and I didn’t put it together until I had done several pieces that my designs are the patterns I saw as a child.” While the Tumbling Block line had severe edges, Charles has also crafted chairs and tables that have more spherical lines to them. “I’m crazy about egg shapes and round shapes, I ate an egg every morning when I was a kid. I had to get the eggs out of the chicken coop on the farm.”

Generous, spirited, curious, and emphatically strong, what you see in Charles now is not only a glimmer in his eye that still has an infinite amount of designs in his mind, but someone who wants to give. He is inspired by and inquisitive about other people and artists. One day in April Charles walked into Merchant Shop on Lincoln Boulevard right on the cusp of Santa Monica and Venice Beach. Shop owner and Venice staple, Denise Portmans, had known of Charles’s work for years and turned out she had one of his pieces there in the shop. Charles then learned of the gallery next door that Denise had recently opened with her daughter, artist Sara Marlowe Hall. As it happened Sara was in the process of hosting an all neon group show at Merchant Gallery — the perfect bedfellow for Charles’s work. The group show, aptly titled BENT, featured neon designs from artists of all different disciplines. The artwork interacted with the vivid textures of Charles’s chairs, tables, and sculptures to add another dimension and reflection to the work that hung on the walls. Charles’s youthful spirit of play and exploration, born in the chicken coops of Bloomington, Indiana, had found another corner of the world to come alive in.